The evidence we should trust: Part A

Evidence-based means...uhm, what?

Editor’s note: This is the first of a multi-part series in which we examine the relative importance of evidence for guiding practice in education. The thesis is that explicit guidance about instructional practices primarily comes from experimental studies examining objective outcomes. It is an opinion piece, so some readers may disagree with the thrust. That’s OK…and, if you disagree, please explain why. Buckle up and read on…. Also please note that I mistakenly sent a draft of this post to subscribers on JohnL

If you, Dear Readers of Special Education Today, have encountered headlines, stories, posts, and notes about “the science X” (where “X” can take on values such as “reading,” “math,” “learning,” and plenty more), this post is for you. As you know, there’s a ginormous amount of talk “out there” about evidence-based education. Being someone who’s concerned about teaching, I wonder about the implications for instruction of these statements.

When I see titles or ledes that use these like “science of reading,” I often take a closer look at the sources. I wonder, whether the descriptions I see touting “evidence-based teaching,” are based on evidence that I would consider strong or loosey-goosey or even lousy. And, as I feel my skeptical hackles rising, I wonder: “Is this the real deal?” Then I pause and ask myself, “or is it just another extrapolation from some sorta-kinda study?”

To be sure, a lot of advocates and experts can claim the they are basing their recommendations on evidence. It’s sort of de rigueur these days to drop the phrase “evidence-based.” Adocates often—yay!—refer to actual published studies. But too often the evidence to which people refer is yesterday’s meme…uhm…well, more accurately…🐴💩.

But some of it isn’t pony poop. Research may be ill-conceived or ill-executed. Ugh. It may even be well intentioned but, flawed. Even highly qualified researchers may make mistakes. Some of it is really quite credible scientific work. And I am happy to be contributing to efforts by groups such as the Open Science group to promote transparency and openness of research. However, regardless of how solid studies may be, they still may have only a weak or removed connection to instructional practice.

A guide to discerning what research is important.

So, I’m writing about my thinking regarding evidence. What evidence matters the most for instruction. What evidence is not ponypoop? Is some of the evidence quite trustworthy in itself, but maybe only of lessor relevance to educational activities, to instruction?

Here I’m going to provide a preliminary examination of the kinds of evidence that I think should guide educational (and I include special educational) practices. This is an exposé of what evidence should and should not be used to guide teaching.

As readers will know, I have a bias for what I consider effective practices, meaning those approaches, methods, procedures, techniques, materials, and curricula that produce better outcomes for students. If you’re not interested in objectively demonstrable better outcomes, you should probably skip the remainder of this post.

That is to say, if you don’t care about outcomes for students, this content is not for you. If you think kids’ achievement in literacy, numeracy, social relations, oral and written expression, and such is unimportant, press delete. Giving a damn about those outcomes is requisite for groking this post. The fundamental idea here is that we educators want to employ methods, adopt curricula, use practices, implement procedures, and—essentially—help kids do well.

So, we educators should should look to research that tests whether methods, curricula, practices, and procedures cause better (or worse) outcomes for our kids. A lot of other research, however methodologically pristine, is way less relevant for guiding instructional practice.

What counts as effective practices?

To be sure, there are broad policies that are relevant in the conversation about effective practices.1 For example, in US special education, there is a legal emphasis on “free and appropriate education.” That’s a policy. We can test the extent to which it is being achieved (good idea), though it is damn difficult to examine its effects with much scientific certainty.2

But, this post is about what educational practices (programs, methods, procedures, etc.) have evidentiary bases, not what policies are good or goofy. Here I plan to talk about what transpires between teachers and students (i.e., the teaching). What do teachers do? What teaching actions affect students’s outcomes?

It’s not about attitudes, theories, purposes, or intentions. At the least, each of those have to actionalized into teaching methods. Asked another way:

What teaching actions used by educators have beneficial effects on students’ outcomes? No mater what flavor of constructivism teachers espouse, what they do in teaching is what I’m examining.

Whatever version of instrucitivsm teachers espouse, what are the effects of actions that they take on their students’ outcomes?

Whatever flavor of discovery learning teachers espouse, what actions that they take have what effects on their students’ outcomes?

Back to the big picture: In summary I’m examining what teaching actions work.

Work?

What do I mean by “work?” This is really important.

In business, “works” is a synonym for “makes money.” You can hear business people talking about whether a product, service, or campaign “worked”:

“Man, our new menu really worked. People were eating it up!”

“Listen here: We have an advertising program that works. We’ll have people buying your soap like it is going out of style.”

“Oh, yessss! This reading system really works! At the conferences, the teachers just swarm our booths. It works!”

So, when a publishing company representative talks about how well her company’s new, computer-based reading program “works,” I’m going to be a tad wary. To me, I care little about how popular it is, how well it sells. I want to know how well kids’ reading improves when they use that fancy (and often expensive!) product. That is, does it work in the sense of producing better learner outcomes.

I want to know how well kids’ reading improves when they use that fancy (and often expensive!) product. That is, does it work in the sense of producing better learner outcomes.

Distinguishing between whether some method (practice, technique, etc.) is popular and whether it causes improved performance is a fundamental aspect of identifying which practices we should employ in teaching our kids. It’s easy to conclude that, because everybody is doing it, it must work.

I do not see popularity as an especially important index of effectiveness. Popularity and effectiveness may be correlated. We can argue that if something was not objectively effective, reasoning educators wouldn’t use it. We can argue that if something actually does work, then it ought to be popular. But, whether something is or is not popular does not mean that it works objectively.

Indeed, the popularity question hints at an important idea that is just a couple of paragraphs over the horizon. That idea is that some research results require us to build bridges or stiles to have a path from the research to the practice.

So, think about this: What research provides guidance to educators about what they should do? Here “educators” refers both to we special educators and to our brethren in general education. The reasoning I’m presenting in this post is equally applicable, regardless of whether one is talking about practice in a general or a special education setting, regardless of whether one has special or general education training. The focus of this series of posts is about evidence-based practices. (Full stop.)

Levels of evidence

So, I am going to argue that some evidence about guiding educational practice is more useful than other evidence. Think of two (make believe) studies:

Johannesburg and colleagues studied children’s prosody when they read a passage of fiction for the first time. In a balanced and carefully executed study, they compared three different fluency interventions. They found that fluency Method R and Method M helped students read marginally better, but that students who received Method W read with nearly twice as much expression and animation than the others.

White et al. studied the same three fluency methods. They interviewed > 450 teachers with experience in literacy instruction as a part of a larger study. Among their teachers almost all said they were familiar with the three methods. The overwhelming majority of the teachers said that they would recommend Method W to their colleagues.

Which study has greater implications for guiding instruction? If your answer is the latter study, then you apparently do not see as much credence in children’s outcomes as I do.

Depending on people’s opinions of what works—no matter how honest and strongly held those opinions are—requites a heckuva a lot more reaching, stretching, bridging to draw a conclusion about whether a curriculum, practice, method, etc. improves students’ outcomes.

Much of this argument is logical, but please note that I plan to focus on arguments that are based on facts. Indeed, that is a meta-idea for this entire post. One must advance reasoned arguments that are predicated on facts.

faulty facts with sloppy reasoning = faulty recommendations about teaching

faulty facts, with good reasoning = faulty recommendations about teaching

trusty facts with sloppy reasoning = faulty recommendations about teaching

trusty facts with good reasoning = what we want

Sorts of evidence

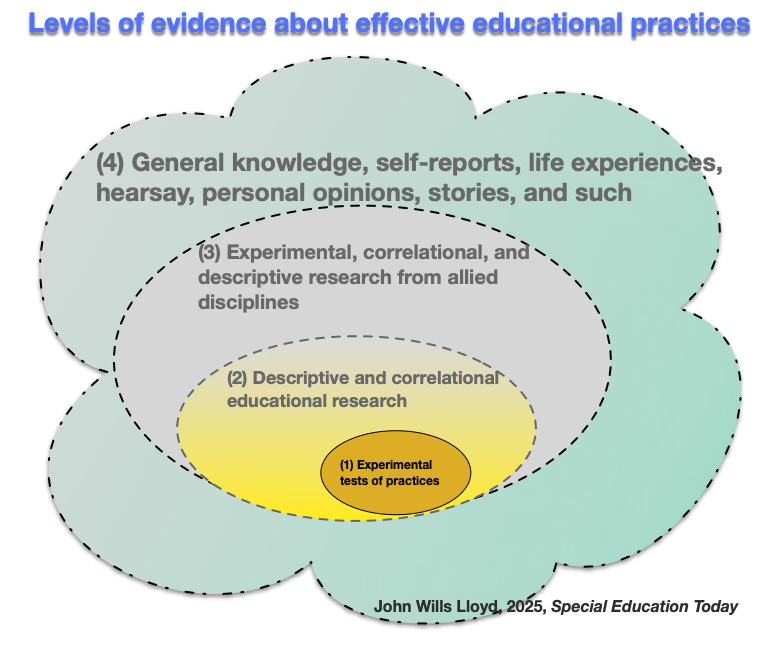

So, some evidence requires a lot less rationalizing to be applicable in saying something works. What are those sorts of evidence? Well that’s the topic of the next installment in this series. But the accompanying image gives some hints about my answer to that question.

References

Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2008). Nonexperimental quantitative research and its role in guiding instruction. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44(2), 98-104.

Hanushek E. A., Kain J. F., Rivkin S. G. (2002). Inferring program effects for special populations: Does special education raise achievement for students with disabilities? Review of Economics & Statistics, 84(4), 584–599. https://doi.org/d54s8m

Hurwitz S., Cohen E. D., Perry B. L. (2021). Special education is associated with reduced odds of school discipline among students with disabilities. Educational Researcher, 50(2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X20982589

Hurwitz S., Perry B., Cohen E. D., Skiba R. (2020). Special education and individualized academic growth: A longitudinal assessment of outcomes for students with disabilities. American Educational Research Journal, 57(2), 576–611. https://doi.org/gjkx2n

Lloyd, J. W., Pullen, P. C., Tankersley, M., & Lloyd, P. A. (2006). Critical dimensions of experimental studies and research syntheses that help define effective practices. In B. G. Cook and B. R. Shermer (Eds.) What is special about special education: The role of evidence-based practices (pp. 136-153). Pro-Ed.

O’Hagan, K. G., & Stiefel, L. (2024). Does special sducation work? A systematic literature review of evidence from administrative data. Remedial and Special Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325241244485

Rumrill, P. D., Jr., Cook, B. G., & Stevenson, N. A. (2020). Research in special education: Designs, methods, and applications. Charles C. Thomas.

Slocum, T. A., Spencer, T. D., & Detrich, R. (2012). Best available evidence: Three complementary approaches. Education and Treatment of Children, 35(2), 153-181.

Footnotes

As I worked on this post, I consulted some excellent treatments of some of the issues I shall discuss. I shall not sprinkle references into the text in the usual academic way. However, readers should know that they can obtain different perspectives on many of the matters I discuss from from other sources. Please consult Cook and Cook (2008); Lloyd et al., (2006); Rumrill et al., 2020); and Slocum et al. (2012) for better written, more well-reasoned, more professional, less snarky treatments of these matters.

Just think about this for a moment. Are there any senior administrators who would like to propose a study comparing FAPE to no-FAPE? There are, to be sure, some sophisticated studies that have examined whether special education is beneficial (