Azrin & Lindsley studied whether children learn to cooperate when it is reinforced

Would you be surprised if it worked in 15 min?

So, people talk about a lot of human traits. There’s intelligence, compassion and empathy, creativity…on and on. Of course, these are traits, and we say that someone has the trait based on her or his actions. For pretty much each of these, it’s possible to provide operational examples (i.e., behaviors) that illustrate them. But…wait! If they’re just behaviors, can’t we actually teach them?

Answer: “Yes.” Traits are just human-invented categorizations of behavior—our interpretations of our observations. And, once we’re senstive to looking for instances of those traits, why, voilà, there they are!

But, what if kids just learned instances of the behavior simply by receiving reinforcement when they exhibited those behaviors? Well, in the mid-1950s two researchers, Nathan(Azrin and Ogden Lindsley (1956) showed how it could happen.

Setting

Here’s the set up: Researchers invite two volunteer children (same age, 7- to 12-years old, and sex) to sit at a table in a room and “play a game” (I know! It sounds trite, but that’s the wording used). A researcher took the children into a room and seated them at opposite sides of a table that was divided by wire mesh; each child could see what the other child was doing but could not operate on the other’s materials. The accompanying image shows stick figures sitting at a line-drawn table, as used in the experiment.

The experimenter provided these instructions:

“This is a game. You can play the game any way your want to or do anything else that you want to do. This is how the game works: Put both sticks (styli) into all three of the holes.” (This sentence was repeated until both styli had been placed in the three available holes.) “While you are in this room some of these” (the experimenter (E) held out several jelly beams) “will drop into this cup. You can eat them here if you want to or you can take them home with you.” The instructions were then repeated without reply to any questions, after which E said: “I am leaving the room now; you can play any game that you want to while I am gone.” E then left the room until the end of the experimental session.

Method

The experimenter, as one can see from the instructions, did not read the students a story about cooperation, tell them to work toward any goal, request that they reflect on any human emotions or traits, explain the benefits and history of cooperation, or explain why or when the jelly beans would fall into the cup, etc. But, and here’s an important part, if both children put their styli into corresponding holes within a fraction (i.e., a 25th) of a second, a light flashed and a (one!) jelly bean fell into the cup.

Of course, behind the scenes, the researchers were recording “cooperative” responses (i.e., those times when the both styli hit the corresponding holes at almost the same time) and not-cooperative responses (maybe different holes; maybe the same holes but not simultaneously); they also observed students’ sharing of the jelly beans and vocalizations during the sessions. Also, every 15 min the researchers surreptitiously changed the frequency of when the jelly beans were delivered (i.e., altered the schedule of reinforcement): First (A), every cooperative response caused a jelly bean to come down the tube and into the cup; second (B), no cooperative responses were rewarded; third (A), each cooperative response was again rewarded (the duration of this period varied).

Results

So, here’s what happened.

During the first few minutes of the A condition, the students in each team cooperated on average about 5.5 times per minute; during the last 3 min of the phase, they cooperated 17.5 times per minute.

During the last 3 min of the B condition, they cooperated about 1.5 times per minute on average.

During the last 3 min of the second A phase, they cooperated about 17.5 times per minute

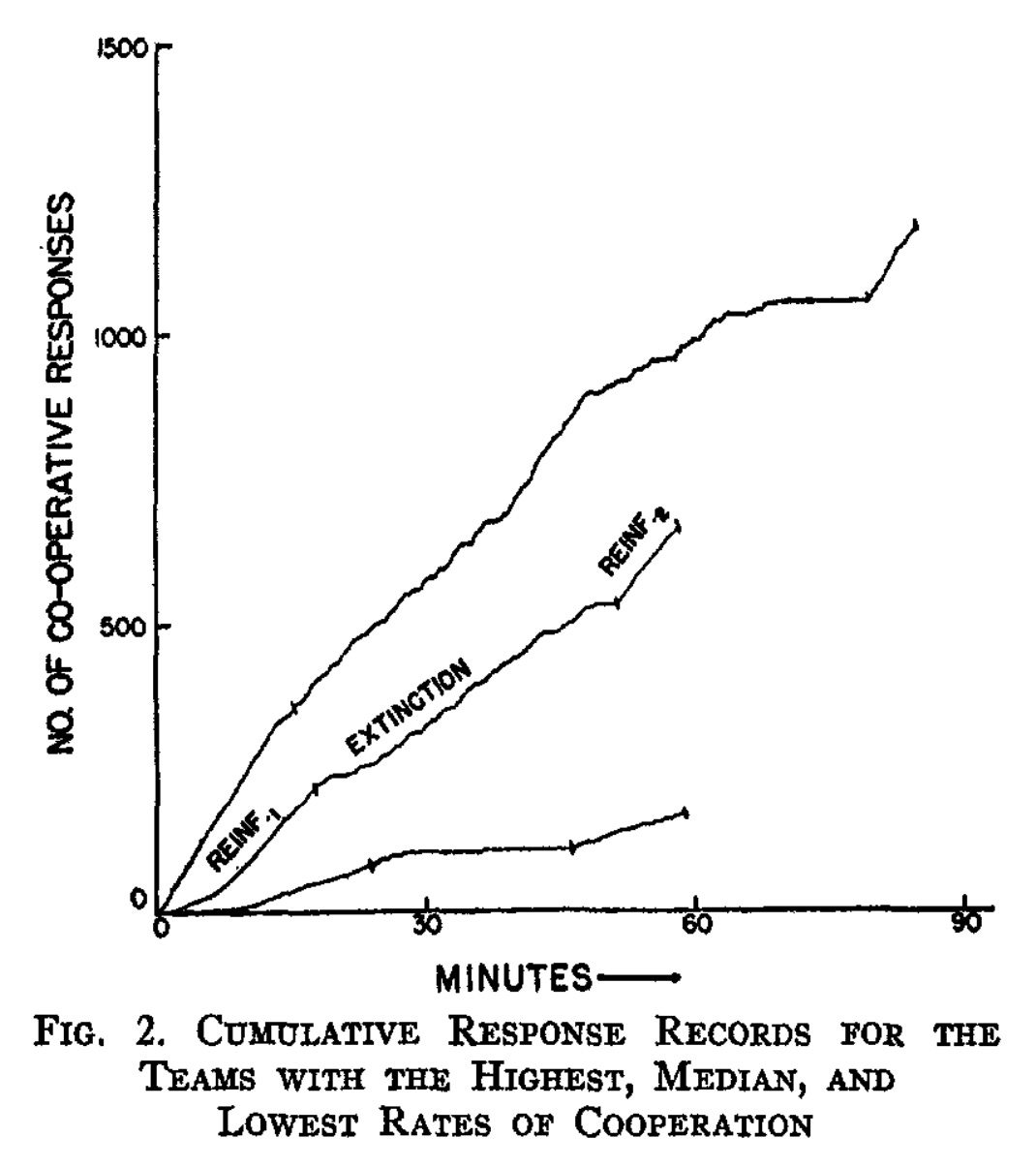

Some teams, as illustrated in Figure 2, learned to cooperate quickly, but others took more time. (Note: The small vertical marks on each curve shown when the conditions changed from A to B and back to A.)

Interpretations

OK, let’s stay close to the data here. Let’s leave the extrapolations to human traits, Lord of the Flies, and development of the hominid species for later.

Azrin and Lindsley showed that, left to their own devise in a situation where making similar responses was reinforced, children quickly learned to cooperate. They did not require lots of verbal explanations, demonstrations, or etc. to acquire this relatively important social behavior. The researchers simply had to create an environment in which cooperation was the name of the game.

Please do not take the foregoing interpretation too far, though. The children did not learn “how to be cooperative”; they learned how to cooperate in this particular situation. That is, they didn’t develop a trait, they learned to behave in ways that we adults can call cooperative.

Importantly, please do not run with the idea that educators should buy tables with electronic styli, mesh screens, and jelly-ball-catching cups as a way of teaching the trait (strategy) of cooperation. Doing that would be an “ooops!” Educators have adopted similarly mistaken approaches in hopes of improving—just to name a few—visual perception, reading readiness, linguistic competence, reading comprehension strategies, and a host of other ideas.

Now, some readers will wonder what the childen in the experiment said to each other. Students quickly developed “leader-follower strategies” (p. 101), but the report does not make clear whether the same individual routinely took one or the other role in discussing when to put the styli into which hole.

Some readers will wonder what happened when one student took the jelly beans before the other could do so. What happened when one “hogged” the edibles? “With two teams, one member at first took all the candy until the other member refused too cooperate. When verbal agreement was reached in these two teams, the members then cooperated and divided the candy” (p. 101)

The big take-away for me: Educators and parents should always be alert for instances when children cooperate, and they should be sure to make those instances of cooperative behavior happy, joyous, successful...in short, reinforcing. Now, it is okay to think about applying this idea to other traits!

For related studies about communication, imitation, and self-awareness, see “The Columban Simulations,” a series of studies in which Robert Epstein (1981) and B. F. Skinner taught pigeons to tell each other the colors of hidden lights. They posted a two-part video explaining the project over on YouTube; see Part 1, especially.

Sources

Azrin, N. H., & Lindsley, O. R. (1956). The reinforcement of cooperation between children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 52, 100-103. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0042490 [APA paywall]

Epstein, R. (1981). On pigeons and people: A preliminary look at the Columban Simulation Project. Behavior Analyst, 4, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391851 [paywall]